If you have been reading my blog recently then you know my economic view of the world is based on Money Realism. While this provides a good foundation for understanding the monetary system, predictions may vary among its adherents. Simply put, I am slightly more bearish on the US economy than Cullen is.

Cullen points to three improving macro indicators: retail sales, initial jobless claims and manufacturing production. The problem with looking at these indicators is that they are all lagging and only offer the historical trend. One must look at forward looking markets or leading indicators. I asked Cullen if he looks at forward indicators and if they are showing any divergence from the lagging indicators to which he responded:

"My general view is that the macro picture in the USA has not changed in recent weeks and that Mister Market was just having an Ebola and Europe scare…"

It appears Cullen has a sanguine outlook for the US economy but let me tell you what I am seeing...

The bond market is one forward looking indicator and it is predicting low inflation. Lower inflation usually means a lack of demand in the economy and entails an extension of the accommodative monetary policy set by the Fed. In other words this lowers the probability of interest rate increases in the future.

|

| Note the sharp drop in the back end of the US inflation curve over recent months |

dynamics in housing not posive, in UK as well as in US ...hope for the best, but https://t.co/GYvmQXlxaV pic.twitter.com/OcWNIDndvf

— Aurelija Augulyte (@auaurelija) October 8, 2014

Finally, the collapse in oil prices is telling you that the global economy is stagnating and that inflation is not likely to be a concern in the short to medium term (lower inflation = economy not operating at full capacity):

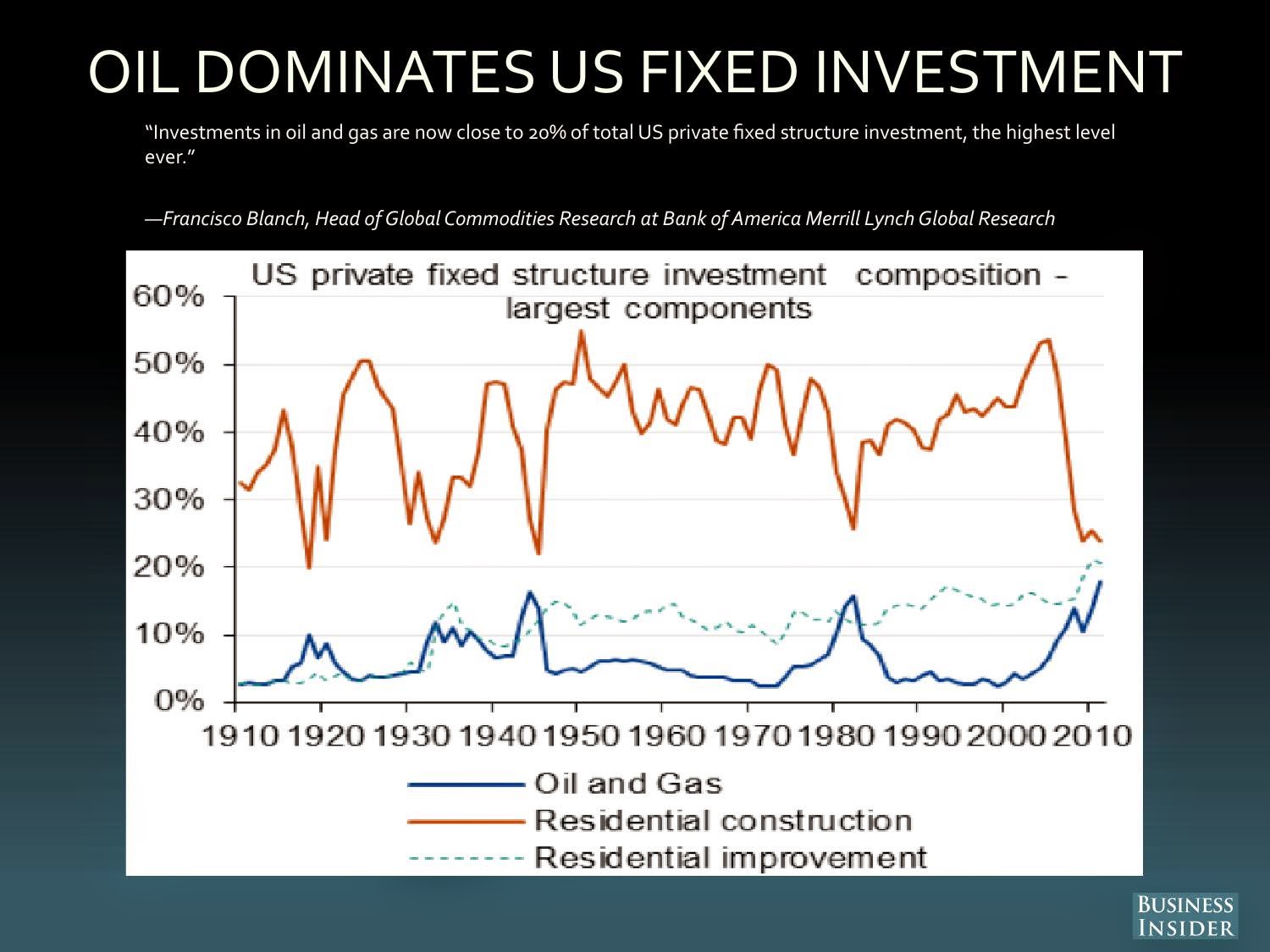

The other reason the US economy will slow in the short-medium term is that a significant part of the US economic recovery has been driven by fixed capital investment in the oil and gas industry. With oil prices falling, we are likely to see less investment activity. It depends how much further oil prices fall, but WTI would need to fall below $80 before we start seeing projects suspended.

Of course falling oil prices are also beneficial to US consumers who will be paying less to fill up their cars. It is often remarked that a falling oil price is like a tax cut for consumers who will now have higher discretionary incomes. The falling oil price is a mixed bag for growth but inflation is definitely less of a problem in the short-term.

There are other macro risks including geopolitics and further strength in the USD, which would slow down the US recovery. Until those risk scenarios materialise, the US economy should continue to heal albeit at a slower pace. The Fed is unlikely to increase rates until wages begin to rise and inflation becomes a clear problem. Given the perception of a fragile recovery, the Fed will be reluctant to raise the Fed Funds Rate/IOER early. I do not see the Fed increasing interest rates in the first half of 2015 and are now less likely to hike rates in the second half of 2015.

To summarise:

- Forward looking indicators are warning that the US economy's momentum is slowing along with the global economy

- Inflation less of a concern given market expectations and falling oil prices

- Deflationary forces will prevent the Fed from increasing interest rates in the first half of 2015

EDIT: In April 2015, Cullen Roche agrees that the US economy "appears to be softening" and it "would be wise to wait on rate increases".